Designer and TV presenter Kevin McCloud once said that Japanese architecture and urban planning in Japan was just about the ugliest he'd ever seen.

I know why he'd say that relating to much urban building, but I disagree.

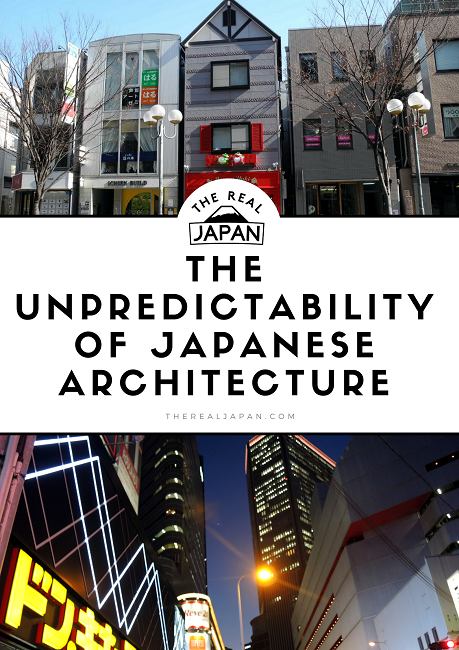

For me, what I find so consistently rewarding about urban architecture you find when travelling around Japan, is the complete unpredictability of what could pop up next.

The unpredictability of (modern) Japanese architecture

Chances are that within a single city block there can be a different style of architectural design in every building the the block!

In many modern Japanese cities, don't be surprised to find a modest, wooden Shinto shrine nestled in between the avant garde steel and glass towers.

Devastation of colossal bombing

The Japanese have a very pragmatic approach to living life. Fostered, no doubt, at least in part by the turbulent nature of the islands they inhabit. Permanency, particularly with buildings, is hard to maintain in the most earthquake-prone country on the planet.

And after the devastation of colossal bombing of the country that ended World War II, the emphasis was on rebuilding as quickly as possible to re-house the population, with little regard for aesthetics.

In Japan, ancient historical sites are frequently rebuilt. Highly-prized religious buildings painstakingly taken apart, moved and reassembled in order to preserve them.

The hand of mother nature

The societal acceptance of the transient nature of humankind and, therefore, of all the things we create, but especially our architecture, inevitably get reflected in the decision-making process of urban planning.

Anything given the go-ahead could, in theory at least, be gone in a couple of years, discarded by the hand of mother nature.

This contrasts with most western countries, but most particularly with the one of my birth – England. In England there is as deep-seated cultural obsession with preserving (and perpetuating) the architecture of the past.

Higgledy piggledy unpredictability

So much so, that none other than (the then) Prince Charles (he of the Royal Family), well-known for his hatred (and that is not too strong an adjective) of most modern architecture, directly involved himself in the development of Poundbury.

This is a 'new town' for people who want to (literally) live in the past. It was built in Dorset on land owned by the Duchy of Cornwall (aka then HRH Prince Charles).

Whilst England can boast some fine examples of modern architecture, you'd be hard-pressed to find any examples of the higgledy piggledy unpredictability of Japanese streets.

The suburbs of England

The first home I owned was the classic, mid-terrace, traditional Victorian 'two up, two down' house. The suburbs of England are still dominated by the utilitarian, serried rows of them. Most of which went up before the turn of the century.

Entire city blocks of housing, especially associated with the north of England, comprise of row upon regimented row of the things.

Indeed, the opening credit sequence of world's longest running TV soap drama Coronation Street, set in the fictional Weatherfield (based on the real town of Salford in England), has long used the very image of terraced housing both in its opening and closing credits. Serving as the backdrop to the dramatic stories of the troubled inhabitants.

Little surprise then, when a Japanese friend who, before she first came to England, and based on what she had seen in the media, genuinely believed that the all housing in England comprised those serried rows of terraces.

Visiting my then house for the first time, a fine example of precisely that, it was hard to dissuade her of that belief!

The nail that stands out

There's a curious dynamic at play here.

To outsiders, the Japanese, as a race and society, are viewed (in part because they are typically portrayed) as a homogeneous conforming mass. Where the distinctive individual is seen either in a unfavourable or, at best, 'quirky' light. And there's some truth in this.

The Japanese even have their own maxim for that: “Deru kui wa utareru" (The nail that stands out must be hammered down).

Curious that it uses a construction metaphor, as when it comes to urban Japanese architecture, it's often the complete opposite. It is as if virtually anything goes; the more incongruous/inconsistent a new building is from what has gone before, and stands either side, the better.

Cost-efficient boxes

Is this due to the cost of land meaning that property developers cannot afford to buy swathes of land and plonk the same, uniform (if cost-efficient) boxes on it? Are they instead forced to simply come up with something that fits into a narrow site without having to concern themselves with the 'local vernacular'.

Is Japanese architecture (and therefore Japanese architects) simply more unfettered, either in their design flair or by local planning ordinances, than in other countries? I don't know.

The most unconventional and unpredictable

But, consequently, and ironically, in stark contrast to the widely-held perceptions of the differences between Japanese and Western society, it is the Japanese that end up having the most unconventional and unpredictable built environments.

Whereas their Western counterparts happily sit in their boxes, that each look exactly like the one next door, in the next street and the next block, and reflect on their 'individualism'.

A related footnote: a fascinating (and striking) statistic emerged as far back as 2009 in a report* about the average house size in countries around the world. It found that the size of the average house in the UK was smaller than its equivalent in Japan (33m² in the UK compared with 35m² in Japan).

Makes you think about what you think you know, doesn't it?

*Source: http://shrinkthatfootprint.com/how-big-is-a-house

What strikes you about modern Japanese architecture?

Do you disagree with my views?

Let me know by leaving a comment below...

About the Author

A writer and publisher from England, Rob has been exploring Japan’s islands since 2000. He specialises in travelling off the beaten track, whether on remote atolls or in the hidden streets of major cities. He’s the founder of TheRealJapan.com.

Further Related Guides

Japan Architecture Tours An Insider’s Review 7 Wabunka Experiences

Enjoyed this article? Then please share this image:

Fascinating post Rob. I figure that utility counts most in a place like Japan. If earthquakes are routine and big ones not the rarest of rare events, building will be a little less focused on prettiness, per se. Factor in how entire cities became wiped off of the map due to the madness of humans and I understand why the architecture would be highly unpredictable.

Ryan

Thanks Ryan. I’m passionate about architecture, so I enjoyed writing this, from a very personal perspective. Glad to hear you enjoyed it so much.